An interesting study on predictors of youth smoking was published this week in the journal Annals of Family Medicine. The study examines whether perceived availability of cigarettes is a strong predictor of whether youth will start smoking.

An interesting study on predictors of youth smoking was published this week in the journal Annals of Family Medicine. The study examines whether perceived availability of cigarettes is a strong predictor of whether youth will start smoking. Tuesday, July 15, 2008

New study on youth smoking and perceived availability

An interesting study on predictors of youth smoking was published this week in the journal Annals of Family Medicine. The study examines whether perceived availability of cigarettes is a strong predictor of whether youth will start smoking.

An interesting study on predictors of youth smoking was published this week in the journal Annals of Family Medicine. The study examines whether perceived availability of cigarettes is a strong predictor of whether youth will start smoking. Monday, July 14, 2008

New vision for schools?

It sounds a lot like the idea of Community Learning Centers, only expanded and taken to scale as a national model rather than scattered sites that worry about losing or renewing funding. Granted, this is coming from the AFT rather than from the Department of Education, which still strongly supports No Child Left Behind. But it will be interesting to see in the comming months, particularly with a shift in presidential administration in one direction or the other, what happens with the national vision for education, and whether this idea takes sway.

I'm also curious what you think of the idea.

Friday, July 11, 2008

Storytelling II: This American Life highlights Lucia Lopez

As discussed yesterday, we have seen over and over again how programming that allows youth to tell their own stories, particularly in a collaborative manner, is transformative. Stories give youth a way to express where they want to be, what they've been through, what's been helpful, and how far they've come.

As discussed yesterday, we have seen over and over again how programming that allows youth to tell their own stories, particularly in a collaborative manner, is transformative. Stories give youth a way to express where they want to be, what they've been through, what's been helpful, and how far they've come. To hear a startlingly well-told, real-life example of the transformational power of autobiographical storytelling, listen to Act II of this episode of the radio show This American Life.

In her own words, it details the story of Lucia Lopez, a young woman involved in gangs in Chicago. Your heart breaks, listening to her tell frankly about her childhood, "Since I was a little girl growing up, I never had an okay day."

By a fluke, she falls into a youth theatre program and lands an opportunity to tell her life story on stage as part of a play. Through storytelling, Lucia changes herself from someone enmeshed in a world of violence to someone in control of her own life.

She says "I would tell people, 'What are you looking at? Do you have a problem? Don't be lookin' at me like that because, you know, something could kick off...'" She feels like she needs to beat up anyone who looks at her. Later, on stage, she realizes that hundreds of people are looking at her... and they're supposed to. Describing this transformation, she giggles and says, "I'll be like, wow. I guess I gotta get used to it. I can't be attacking everyone who's looking at me during the play!"

This episode was recorded a few years ago, but the message is timely.

I have to applaud Ira Glass for his frank statements about the importance of afterschool programs in this episode. He references a study Shirley Brice Heath conducted over ten years, studying 120 afterschool programs. She stumbled upon a finding that surprised even her; Ira Glass describes,

It is still hard to advocate for funding for arts programs, arguably even harder than when this program was recorded. And yet anyone who has led or participated in such programs can attest to their power."Arts programs were more effective at changing kids lives than any other kind of program for kids. More than sports and academic programs, more than community service programs. The art kids not tended to come from worse backgrounds than kids in the other programs... but after being in these programs, they became kids who were more likely to read for pleasure, they were more likely to be in honors societies, get academic honors, they were more entrepreneurial, they started projects, they were more willing to teach other kids.

"Shirley Brice Heath said that's because the arts programs tended to involve kids in more collaborations with each other. They were just doing harder stuff. And critiquing it, and making big plans, and contingency plans, and reevaluating plans, and they learned all these verbal skills.

"Her study also showed that although those programs are the most effective at helping the kids who are the most at-risk in our society, they have a terrible time staying afloat. Nine out of ten of them can't find funding sources and die within eight years."

Lucia herself agrees that the fact that she was in an arts program specifically was essential to her transformation. She describes doing this play as a tool she used to look at everything that had happened in her life, let it go.

At the end of this episode segment, Lucia performs a short narrative scene from her own play. Don't miss it.

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Storytelling: an effective resiliency tool for at-risk youth?

A recent study released last month in the journal Child and Youth Care Forum examined the role participatory storytelling can play in programming for at-risk youth. Specifically, they looked at two things: how storytelling can help program planners evaluate what parts of their programs work best, and how it can help youth in the programs build resiliency and change their lives for the better.

A recent study released last month in the journal Child and Youth Care Forum examined the role participatory storytelling can play in programming for at-risk youth. Specifically, they looked at two things: how storytelling can help program planners evaluate what parts of their programs work best, and how it can help youth in the programs build resiliency and change their lives for the better. The researchers added a storytelling project into a diverse spread of summer programs, and selected an average pool of participants from each program to join the storytelling component. Through assorted creative means, participants were encouraged to tell their own stories and the stories of made-up characters participating in the same experiences they were undergoing in their own programs. Youth engaging in storytelling reported dramatic changes in their levels of risky behavior and striking increases in their sense of optimism about the future. Notably, some of the risk behaviors reduced through storytelling were not shown to be reduced effectively by other methods, such as telling youth that certain behaviors are risky.

I'm not surprised. You probably aren't either if you've ever directed autobiographical storytelling with kids, or led quality reflection activities after a service-learning project, or heard campers at a summer-closing campfire tearfully tell the stories of their best memory at camp.

The reason is that narrating one's own experiences of growth and transformation solidifies those experiences. People learn from reflecting on experiences just as much as they learn from the experiences themselves. Reflection, narration and storytelling tie the pieces together, and solidify them through articulation. The creative action of telling one's own story, or someone else's, has been shown to be empowering and transformative, time and time again.

My only concern reading this study would be whether youth might tell stories of their own positive transformations or goals for the future because they sense that's what the adults want to hear. I don't think that's the case in this study, given that some of the statements were strongly personal in nature, but it would be worth further research. Kids and youth, whether in a classroom or program, are intuitive when it comes to questions we ask; they know there's an answer we want to hear, but they also get comfortable over time, and are frank about what they feel.

And it's that frankness that's essential to and empowering about storytelling. Telling youth to behave differently, or telling them who they are isn't especially useful or empowering, but creating a space for youth to tell their own stories enables them to tell us what works, and to make it happen with our support.

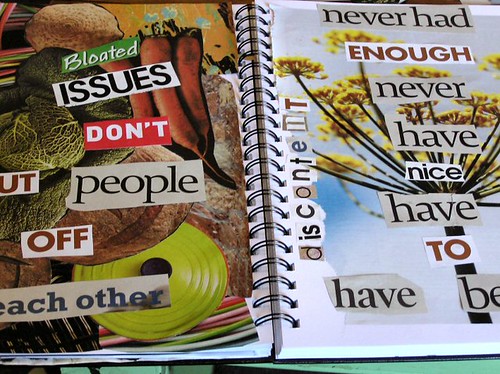

Thanks to pupski for the Creative Commons photo.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities III

This is part 3, the final piece, in an ongoing series featuring SOAR's paper on including children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school and youth development programs. Inclusion means creating or sustaining programs for children and youth to interact together, across all lines of ability and development. This piece continues where part 2 left off.

This is part 3, the final piece, in an ongoing series featuring SOAR's paper on including children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school and youth development programs. Inclusion means creating or sustaining programs for children and youth to interact together, across all lines of ability and development. This piece continues where part 2 left off.KNOWLEDGEABLE STAFF, PROPER RATIOS

Inclusive programs benefit from hiring staff with experience, knowledge and skills specific to supporting children and youth with developmental disabilities. Aside from interacting with participants and program design, such staff members can be helpful in training other staff, in helping the program maintain its ongoing goals of inclusion, and in evaluating areas with room for improvement. To find skilled and knowledgeable staff, programs can build partnerships with other entities. They might look to universities, particularly programs such as special education, nursing, social work, physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, or related fields. They might partner with existing organizations focused on children and youth with disabilities, such as Special Olympics. Summer programs may be able to recruit teachers from special education classrooms, as might other programs that meet outside of school time. Staff members who themselves have disabilities or family members/loved ones with disabilities may provide a perspective about the needs of participants, while being role models and mentors.

Programs must also have adequate resources to help these staff succeed. This includes adequate numbers of staff, opportunities to train other staff members, program supplies, flexibility, and a willingness to adjust programming as needs and creative ideas arise. As with all programs for children and youth, proper ratios are crucial for maintaining a safe environment in an inclusive program. Some children and youth will need one-on-one attention whereas others will simply need staff to be aware of what helps them thrive and succeed. On a case-by-case basis, programs may communicate with each participant’s family to ensure ratios are appropriate.

Staff retention is crucial to success. Support and training are expensive but necessary to helping staff succeed. By setting aside funds, policies, and other priorities for staff support, programs will retain talented, quality staff. Similarly, foundations seeking to support inclusive programs can include or encourage funds to be spent on sufficiently hiring, training, compensating and retaining staff.

TRAINING

Inclusive programming is beneficial for staff without prior experience in this area. Training and working with all participants raises staff awareness and expectations for how children and youth can work together and thrive when in a supportive, well-structured environment.

Not all staff in a program will have expertise in supporting children and youth with developmental disabilities, and may know more about one disability than another. Training is essential, and also provides an opportunity to increase the extent to which youth workers and after-school staff in the field are knowledgeable about these issues. Programs should provide training both before staff are working with participants and on an ongoing basis. Training should include accurate, cutting-edge, respectful information, answer challenging questions, and leave staff prepared to succeed. Training should involve everyone in the process of increasing inclusion.

Training for direct program staff might include:

· Working with children and youth with developmental disabilities

· Fostering cooperation and friendship-building between participants across lines of ability

· Activity ideas

· Scenarios and role-playing

· Respectful behavior management tools

· Opportunities for staff to create or share ideas

· Developmental disabilities/health knowledge/variety of disabilities

· Being flexible/partnering with youth/family on their specific needs

· Safety and risk management

· Effective interaction

· Specific skills related to the program

· Ongoing training, increasingly advanced

· Articles and written material, visual tools, interactive opportunities and other means for meeting the varied learning styles of staff

Training for management staff might include:

· Advocacy for inclusion

· Communication with families of children with and without disabilities

· Supporting staff

· Program visioning and design

· ADA and legal issues

· Determining proper ratios

· Attending trainings intended for direct program staff to increase knowledge and show commitment

Training for the community might include:

- Sharing a successful program model and helping other programs create their own

- Presenting the benefits of inclusion

- Overcoming challenges the program has successfully faced

- Creative program ideas

Programs benefit both from one-time training opportunities and from ongoing consultation, support, and technical assistance.

CREATIVE, FLEXIBLE EXPANSION OF PROGRAMMING

At the core of inclusion, programs need to adjust existing programming or determine which programming is already inclusive. Flexibility, creativity, clarity and communication are all key to inclusion, since there is no one formula that will be suitable for every participant, even with a particular disability. A study of best practices in inclusion lists the three core areas programs need to adapt as: physical environment, activities and games, and time adjustment.[ii] Such adjustment presents opportunities to transform activities or add new ones, determine new ways to manage activity timing and transitions, and create a physical space suitable for all participants. To succeed in programs, children need to understand the rules, feel respected, choose from options they enjoy, and experience the communication methods that work best for them.[iii]

Developmental disabilities encompass a wide range of categories, including autism, Down syndrome, Asperger’s syndrome and others. Children and youth also experience behavioral disorders, emotional disorders, learning disabilities, language limitations, physical disabilities, and health issues.[iv] Within each of these categories, individual people have different abilities and challenges. There will be no one solution or practice that supports every youth, even within a particular developmental disability. Programs must be creative on an ongoing basis, share ideas, and try new things with every individual they serve.

Staff should be trained in effective models for engaging participants in many ways at once, such as multiple senses, interests, and styles of intelligence. Some examples of such methods include the Center for Urban Education’s Framework for Effective Instruction, and Dr. Martin Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences.

Participants learning to build friendships and feel successful in an inclusive program will benefit from non-competitive activities, programming that allows for different paces and learning styles, engages multiple senses, and includes smooth transitions between activities.[v] Additionally, programs will learn from participants how best to support and include them by building relationships with them and their families.

Program design affords an opportunity to use creativity to manage behavior issues. By involving participants in program design and in the definitions and consequences of rule-breaking, children and youth will have a better understanding of, and more investment in their program and its rules. There are numerous strategies for supporting participants through behavioral challenges in the resources listed at the end of this document. These include peer mediation, social skills training, attention for positive behavior, pre-determined cues for concerns about behavior, and smooth transitions between activities to help participants stay engaged.

In practice, there are countless tips to helping various children and youth succeed at activities. Staff can assist children and youth in physical activities they may not be able to do in the same way as some of their peers. Visual cues can help some children and youth when giving directions for an activity. For many more ideas, programs can turn to detailed, practical guides to supporting the needs of children and youth with a range of specific disabilities. For one such guide, see Together We’re Better: A Practical Guide to Including Children of ALL Abilities in Out-of-School Time Programs at the end of this report.

MARKETING AND OUTREACH

With a societal mindset habituated to the idea that there are “mainstream programs” and there are “special-needs programs,” inclusive programs must pay careful attention to outreach. Such programs need to reach families looking for programming for children with specific developmental disabilities as well as families looking for programming for children without disabilities (or for multiple children). To ensure all families feel the program is relevant, safe, and interesting, all families must be kept in mind during outreach and marketing.

Families whose children have special needs may be used to thinking that their children are not welcome in most programs, based on past experiences, and may need to hear specifically that a program is becoming inclusive.[vi] Families can be reached through schools, including special education classrooms, as well as through PTAs, teachers, principals, libraries, health and social service professionals, brochures, flyers, websites, and any other means traditionally used to reach children and youth not already participating in quality programs.

Materials that put the child first are crucial. This is for two reasons. First, paralleling inclusive or “people first” language (e.g. “child who has a disability” rather than “disabled child”), marketing materials should reflect our values of focusing on children themselves rather than their abilities or disabilities. Second, inclusive programs must take care not to alienate any families, including those whose children don’t have disabilities. Marketing materials should focus on the activities, benefits, staff, values, and goals of a program. This information should include statements on inclusion at several points, and use language that makes it clear activities will be suited to participants with multiple learning styles and abilities. Pictures can also send inclusive messages.

When targeting families of children and youth with developmental disabilities, programs may use additional materials, such as a letter about why and how the program is inclusive. A letter may include Q&A for families (including some questions from parents whose children don’t have disabilities), a value statement about inclusion, and stories of past participants who have had positive experiences. Such materials can be helpful to families who are wary from having their child rejected from programs in the past, or who have never placed their child in an inclusive program.

Shared, centralized outreach and visibility benefits all programs. Ideally, a community should have a centralized resource (website, phone number, directory, etc) listing inclusive programs in the area. This allows youth and families to have a choice, and keeps programs truly inclusive by avoiding driving the majority into one program.

ASSESSMENT

Programs and communities can expand their existing evaluation and assessment tools to reflect whether inclusion is happening successfully[vii] and take additional steps to see if inclusion is working. Such steps may include:

SHARE KNOWLEDGE BETWEEN PROGRAMS

Inclusion is about strengthening individual programs and about creating systemic-level change. On a community level, we can increase conversations about inclusion and help multiple programs at once make their programs appropriate for children of a variety of abilities, including developmental disabilities. Programs can help this happen by sharing existing knowledge and successful models, both locally and nationally. For more ideas, see the Training section of this document.

FUNDING/ROLE OF FUNDERS

Funders also play a key role in increasing inclusive practices. To create, maintain, and increase awareness of programs that are inclusive involves a great deal of steps and changes. Some of these require little to no cost, while others can be quite expensive, such as particularly the hiring of additional staff members, training staff in inclusion, or acquiring or modifying program equipment. Funding concerns can be prohibitive for programs interested in expanding their inclusivity.

While some funders prefer focusing their efforts on one program at a time, or must do so due to financial limitations, funding entities should be aware that there is a benefit in multiple inclusive programs in a community developing simultaneously. There are countless underserved children and youth with a range of developmental disabilities in any community whose parents wish to find inclusive programs. When multiple programs develop and outreach at once, families have choices and programs stay truly inclusive.

NEXT STEPS

For programs, collaboratives or communities looking newly to increase inclusion of children and youth with disabilities, the information in this report may be a starting place. A number of the resources listed in the endnotes will provide detailed ideas for inclusion, such as checklists for programs looking to become inclusive, case studies of existing programs or models, evaluation procedures, DVDs , books, and more.

Within King County and other communities, there are myriad individuals at all levels who have knowledge and ideas about increasing inclusion, and these voices should be heard. These include direct service staff who have experience working with children and youth who have developmental disabilities, youth and families themselves, program directors, health professionals, and staff of programs designed specifically for children and youth with special needs. These experts, as well as representatives from the sources cited in this study, will have additional wisdom and insights.

By building collaboratives within and between programs, some of the challenges detailed here will lessen. Programs may feel less daunted to take on the challenges of inclusion because of outside support. Funders may understand the needs and rationale behind inclusion, and support it as a priority. Programs with strong ideas and models in the community may share what they know with the end goal of improving all programs. All entities can continue building from one another’s knowledge toward a shared vision of inclusion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER RESOURCES

The After-School Corporation: www.tascorp.org

Child Care Plus: http://ruralinstitute.umt.edu/childcareplus

Circle of Inclusion (early childhood): http://www.circleofinclusion.org/

Kids Included Together: http://www.kitonline.org

Multiple Intelligences: http://www.ldpride.net/learningstyles.MI.htm

National Conference on Inclusion: www.kitconference.org/

Stumpf, Mitzi, Henderson, Karla, Luken, Karen, Bialeschki, Deb, Casey, Mary II. “4-H Programs with a Focus on Including Youth with Disabilities.” Journal of Extension: Volume 40, Number 2, April, 2002

After the Bell Rings: Developing your Kit for Including All Children. 3rd Annual National Conference on Inclusion. Kids Included Together. 4/19/07.

“The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): A new Way of Thinking: Title III.” Child Care Law Center, 2002.

Mulvihill, Beverly A. PhD, Cotton, Janice N. PhD, Gyaben, Susan L. MPH. “Best practices for inclusive child and adolescent out-of-school care: a review of the literature.” Family & Community Health: Volume 27 (1) January/February/March 2004 p. 52-64.

Siperstein, Gary N., Ph.D., Glick, Gary C., Harada, Coreen M., Bardon, Jennifer Norins, and Parker, Robin C. “Camp Shriver: A model for Including Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Summer Camp.” Camping Magazine, July 2007.

Harper-Whalen, Susan Ed.M., Morris, Sandra L., B.A. “Child Care Plus Curriculum on Inclusion: Facilitator’s Guide.” Child Care Plus. Missoula: The University of Montana, 2000.

National Childcare Campaign Daycare Trust. “Listening to parents of disabled children about childcare.” Department for Children, Schools & Families and the London Development Agency, 2007.

Dunlap, Torrie, BA; Shea, Mary, OTR, MPH. Together We’re Better: A Practical Guide to Including Children of ALL Abilities in Out-of-School Time Programs. San Diego: Kids Included Together, 2004

This report was completed in partnership with the King County Developmental Disabilities Division and with funding support from United Way of King County, the King County Children and Families Commission and the City of Seattle Human Services Department.

[i] Mulvihill et al., 2004

[ii] Mulvihill et al., 2004

[iii] The After-School Corproration, 2005

[iv] Dunlap et al., 2004

[v] The After-School Corproration, 2005

[vi] The After-School Corproration, 2005

[vii] Dunlap et al., 2004

[viii] Siperstein et al., 2007

Thanks to kthypryn for the flickr Creative Commons photo

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

Inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities II

This is part 2 in an ongoing series featuring SOAR's paper on including children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school and youth development programs. Inclusion means creating or sustaining programs for children and youth to interact together, across all lines of ability and development. The sign at the left is not what we might call inclusive.

This is part 2 in an ongoing series featuring SOAR's paper on including children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school and youth development programs. Inclusion means creating or sustaining programs for children and youth to interact together, across all lines of ability and development. The sign at the left is not what we might call inclusive....Continued from July 3rd:

CHANGING POLICY

Programs and communities can articulate their commitments to inclusion through developing and following written policies. At a program level, organizations can include in their mission, values or policy statements about how and why they are inclusive of children with disabilities, (as well as other children and youth who are often disenfranchised). At a community level, local governments, community collaboratives, and networks can make written commitments to inclusion, also focusing on why they value inclusion and what they can do to increase it.

Cities can commit to inclusion by providing support, training, and funding for all programs to become inclusive, just as communities have committed to other large efforts such as accrediting child care centers or ending homelessness. Some communities are already starting to look at this option. In its London-based report Listening to Parents of Disabled Children About Childcare, funded by the Department for Children, Schools & Families and the London Development Agency, the National Childcare Campaign Daycare Trust recommends a goal of “ensuring that every childcare setting in London is disability-friendly.”[i] Such recommendations can expand beyond the childcare world to after-school as well; communities can set goals to help as many local programs as possible become inclusive.

APPROACHES: CHALLENGE-BASED AND ASSET-BASED

· Challenge-based Approach: How to meet basic needs, manage risk, and avoid problems. Focus on safety, barriers, cost, bias, and needs that seem difficult to meet.

In discussions on inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities, it is common to hear about the challenges involved. Parents and caregivers face difficulties finding programs for their children. Advocates work hard to raise awareness and increase funding for inclusive programs. Programs face hurdles as they develop, expand or change.

In programming in particular, the discussion often comes down to overcoming barriers. How will we prevent this child from getting hurt? From feeling isolated? How can we afford more staff? How will we make activities physically accessible? How will we make them understandable to this child? How do we manage behavior issues? Challenges stem from funding, liability issues, safety, old ways of doing things, and difficulty changing attitudes and expectations. Further, programs that are marketed as “inclusive” may not be as popular among families whose children do not have disabilities; there may be an assumption that “inclusive” is code for “primarily or exclusively for children with special needs” or that children and youth without disabilities will not be prioritized. Additionally, such programs face pervasive fear-driven bias against those with disabilities that impacts the willingness of families to send children without disabilities to such programs. Changing attitudes is a long-term, systemic-level project that can feel daunting.

Funding in particular stands out as the largest issue for many programs. Inclusion and support of children with disabilities is very realistically expensive, in terms of staffing, facility changes, program changes, just to name a few areas.

These are all genuine difficulties and must be addressed frankly. Yet, a challenge-based approach misses the positive reasons we create youth development programming in the first place. All children and youth deserve to have places to go outside of school and home where they experience friendship, creativity, leadership, learning, caring adults, interesting activities, and nurturing. By adding an asset-based approach to balance out our challenge-based approach, we keep in mind why we’re creating inclusive programming in the first place. We do this because the programming itself is valuable.

· Asset-based Approach: How to ensure children and youth are getting the beneficial assets, experiences, and opportunities they deserve. Focus on quality, youth involvement, and positive experience.

An asset-based approach reflects the values of inclusion, namely, that all children and youth benefit from positive experiences, and that we benefit as a society from including them. Focusing on assets reminds us that inclusion is beneficial for children both with and without disabilities. Inclusive programs highlight similarities among children and youth across lines of ability.[ii]

Both challenge-based and asset-based approaches are necessary. In the positive light of assets, glossing over challenges can put participants at risk of negative or unsafe experiences. A balance between challenge-based and asset-based approaches sets communities up to succeed.

PARTNERSHIPS AND COLLABORATIONS

Collaboration is useful at all levels of programming, particularly curriculum design and program development. Some groups developing model programs, such as the Intentionally Inclusive 4-H Club Program model of North Carolina, include collaborative partnership from the outset.[iii] Collaboration on an ongoing basis also helps ensure successful programming. At all stages, from curriculum development to program maintenance to sharing of models, partners might include:

- Youth with disabilities (and youth without disabilities)

- Parents and caregivers

- Adults with a range of developmental disabilities who can provide a personal perspective about how programs could have served them better as youth

- Representatives from youth programs, including direct service staff

- Students and specialists from universities working in relevant areas

- Health professionals and specialists

- Home care providers

- Community advocates (individuals or organizations)

- Schools

- Those providing resources to people with developmental disabilities (existing specialized programs, transportation services, educators, etc)

- Funders (foundations and/or corporate sponsors)

- Existing programs

- Facilities for programming (camps, universities, parks, etc)

Including a wide range of stakeholders, particularly the youth and families who will be affected, is triply beneficial. First, programming developed with insights, cautions, and ideas of people coming from each of those perspectives will avoid the pitfalls that might seem obvious to one but not the other. Second, including voices such as youth, families and staff in development sends a powerful message internally and externally that the program in question empowers and comes from the community served. Third, collaboration can be beneficial for outreach and marketing of the program since those developing the program will feel ownership of it, and want it to succeed. Families can spread the word to other families; state professionals can publicize the program within their networks.

YOUTH AND FAMILY INVOLVEMENT

As often-disenfranchised members of society, youth need opportunities to advocate for themselves and other youth, to make decisions about the things that impact them, and to have a voice where usually only adults are heard. These opportunities are part of positive youth development experiences for all youth. Youth with disabilities face a double-whammy of ageism and ableism; not only do they experience the disenfranchisement of being young, they also experience a society that overlooks their ability to think, contribute ideas, and participate in decision making because of their disabilities. This is especially true for youth whose disabilities affect language and communication.

Consequently, it is crucial to include children and youth in program development as well as in determining how best to include them in a given program. Certainly different youth will have different extents to which they can contribute, but all can contribute in a way that is meaningful and realistic for their individual abilities.

Further, youth and families know their own situations, needs, preferences and abilities better than anyone else. Programs will be more likely to succeed at inclusion when knowledge from children, youth, and families is incorporated at all levels.

Older youth and young adults can provide particularly useful perspectives, being able to reflect on what would have made programs better for them when they were young.

Programs should bear in mind that parents and caregivers may have experienced setbacks and challenges when trying to involve their children in programs in the past. Having faced rejection from programs, or because of fears that their children will not be accepted, some parents and caregivers will not inform a program of their child’s disability, or will wait until a late opportunity to do so. Proactively creating a safe, welcoming environment will help parents and caregivers feel comfortable and welcome. Involving parents and caregivers as partners in the program will support and empower them while programs benefit from their knowledge. Some of the resources at the end of this report offer suggestions and scenarios to help programs work with parents and caregivers.

Family support and involvement is an ongoing process. As with any parents or caregivers, programs should communicate successes as well as challenges.[iv] Families will appreciate knowing the ways in which their children are growing and thriving. Just as children and youth can connect with peers through integrated programs, families can connect to other families with children with disabilities as well as with typically-developing children.[v]

When families have the option to be involved as volunteers or assistants, programs will get better results because the family members have become true stakeholders in the process. With work and life schedules, this is not always realistic for all families, and assorted types of optional volunteer and engagement opportunities should be available to match the interests, skills, and time constraints of the families involved.

[i] National Childcare Campaign Daycare Trust. “Listening to parents of disabled children about childcare.” Department for Children, Schools & Families and the London Development Agency, 2007.

[ii] Siperstein et al., 2007

[iii] Stumpf et al., 2002

[iv] Harper-Whalen, Susan Ed.M., Morris, Sandra L., B.A. “Child Care Plus Curriculum on Inclusion: Facilitator’s Guide.” Child Care Plus. Missoula: The University of Montana, 2000.

[v] Mulvihill et al., 2004

Thanks to jbcurio for the flickr Creative Commons photo.

Thursday, July 3, 2008

Inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities I

This series of posts will feature, segment by segment, SOAR's report "Inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school, summer, and youth development programs." Today's is the first segment.

This series of posts will feature, segment by segment, SOAR's report "Inclusion of children and youth with developmental disabilities in after-school, summer, and youth development programs." Today's is the first segment.As our communities work to break down barriers of access, bias, and de-facto segregation, we are finding more ways to identify which children and youth are getting left behind, and how to remedy this. We are increasingly talking about and acting on concerns that children and youth don’t have equal access to the kinds of experiences that help them succeed and thrive.

Inclusion, as defined for the purpose of this report, is the practice of creating and sustaining programs where children and youth with and without disabilities participate together as equals, and which approach their programming with intentionality, commitment, knowledge, and partnership. Advocates for inclusion see a social justice rationale, focusing on how children and youth deserve full access to participation, as well as support from a community that is aware inclusion goes beyond physical accessibility. As The After-School Corporation notes:

Inclusion is a practice and a belief that children with special needs should be able to fully participate, with their typically developing peers, in their school and community by engaging in age-appropriate activities. Inclusion goes beyond making space physically accessible to students with special needs and creates opportunities for meaningful participation for all students.[i]

This type of inclusion is becoming increasingly common. An analysis of inclusive 4-H programs explains:

Rather than offering special programs only for people with disabilities, the trend today is toward providing supports to increase inclusive opportunities within all programs open to the public. For most individuals, the elimination of physical and social barriers reduces the need for special programs. This inclusion, however, involves more than just placing people with disabilities into a group. It involves social interaction as well as physical integration. Providing support expresses an acceptance of a person and their abilities and helps the individual participate at his or her level of independence. Inclusion means altering the environment more than forcing the person with a disability to change.[ii]

Inclusion is a successful means of helping children and youth interact and succeed with their peers across lines of ability, often with impressive results. As the parent of a boy enrolled in a summer camp for children with and without intellectual disabilities noted, “[He] was on the verge of being banned from gym class because he was too competitive and got angry with the other kids. Since he’s come to camp his attitude has changed dramatically. He is so much more patient.”[iii] Inclusion also eliminates the isolation and pigeon-holing that can stem from segregated settings, as well as providing opportunities children and youth otherwise wouldn’t necessarily experience.[iv]

Inclusion is particularly important in out-of-school time programs because of the unique assets such programs provide, such as positive social/emotional development, a nurturing environment for strong friendships, creative opportunities, new experiences, chances to try new things and build skills, and connections with caring adults. These are some of the assets that children and youth with developmental disabilities are not getting as frequently as their peers without disabilities. However, studies show that inclusive out-of-school programs are especially helpful in helping children with and without disabilities interact socially with success, as compared to some school settings, where children and youth with disabilities are more likely to feel socially isolated.[v]

Some types of programs are more likely to practice inclusion than others, but the trend in most out-of-school-time programs shows that more are becoming inclusive or considering inclusion. Some fields, such as summer camping, have shown a gradual increase in inclusive rather than segregated programming.[vi] Still, inclusive opportunities for school-age children and older youth are significantly less prevalent than for their younger peers.[vii]

Inclusion is an ongoing process rather than an end result to be achieved.[viii] Families, programs, youth and communities work together on an ongoing basis to ensure programs are meeting needs and interests. Inclusion should be seamless and smooth, rather than clearly visible to all participants. As a result, inclusion will feel natural to all involved, which is a core value of the concept to begin with.

EMBRACING AN ATTITUDE OF INCLUSION

Inclusion means more than just getting the buy-in of staff; parents of children without disabilities must also be supported in understanding the benefits of inclusion. Fears, concerns, and bias are pervasive, and can be challenging for staff to counteract, especially if the staff themselves have only recently been trained in inclusive practices. New York’s TASC (The After-School Corporation) cautions that programs becoming inclusive can expect to work twice as hard to succeed at inclusion, due to such barriers.[ix]

Everyone has to be bought in for inclusion to succeed. Within an organization, collaborative, or local government, those holding the highest positions must support the concept of inclusion, just as the staff who work with the children and youth directly must also support the idea of inclusion. Those in leadership positions can show their commitment through actions such as attending trainings on inclusion with direct-service staff,[x] or adding staff with disabilities to the program and people with disabilities to the Board of Directors.[xi]

On all levels, from city government and large-scale collaboratives to families and direct program staff, partners and programs must foster an inclusive attitude. On a program level, this means a whole-child approach, where youth development, participation, creativity, and all other traditional components of a quality program come first. As The After-School Corporation (TASC) explains,

Focus on similarities, not differences; strengths, not weaknesses. As you develop your program, consider activities that are noncompetitive, allow all students to experience success, can be adjusted to suit the needs of individual students and allow students to progress at their own pace. Think about how your curriculum can reach everyone.[xii]

Staff can foster an attitude of inclusion among participants by focusing on cooperative activities, offering choices between activities, modeling respect, and coming up with creative roles to include children and youth who might otherwise be left out of or excessively challenged by an activity. While programs may not disclose a child’s disability to other participants without written permission for the parent or guardian,[xiii]

While making a full commitment to inclusion might prove successful for some programs that currently work specifically with children with disabilities, other programs may be more successful building inclusion through “reverse mainstreaming.” This involves adding a few children without disabilities to the program at a time, often siblings, friends and allies of participants in the program. Such a shift may help a program adjust more smoothly.

There are resources available to help programs seeking to become more inclusive. Two of these are particularly useful:

The After-School Corporation (TASC)’s Including Students with Special Needs in After-School Programs (http://www.tascorp.org/content/document/detail/1450/)

Together We’re Better: A Practical Guide to Including Children of ALL Abilities in Out-of-School Time Programs (available from Kids Included Together’s website)

TYPES OF PROGRAMS

A wide variety of programs have successfully increased the extent to which they are inclusive of children and youth with disabilities, including developmental disabilities. Such programs include:

- Traditional before- and after-school programs

- Drop-in programs

- Summer overnight camps

- Summer day camps

- Service-learning programs

- Activities for older youth

- Youth leadership programs

- Sports, arts, and cultural activities

- Child care settings with a programmatic focus

- Other community programs for children and youth

This report addresses both existing programs seeking to become more inclusive and communities wishing to develop new inclusive programs from the ground up. Within the above fields, there are programs at all stages of inclusion.

[i] The After-School Corproration, “Including Students Wtih 2005

[ii] Stumpf, Mitzi, Henderson, Karla, Luken, Karen, Bialeschki, Deb, Casey, Mary II. “4-H Programs with a Focus on Including Youth with Disabilities.” Journal of Extension: Volume 40, Number 2, April, 2002

[iii] Siperstein, Gary N., Ph.D., Glick, Gary C., Harada, Coreen M., Bardon, Jennifer Norins, and Parker, Robin C. “Camp Shriver: A model for Including Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Summer Camp.” Camping Magazine, July 2007.

[iv] Mulvihill, Beverly A. PhD, Cotton, Janice N. PhD, Gyaben, Susan L. MPH. “Best practices for inclusive child and adolescent out-of-school care: a review of the literature.” Family & Community Health: Volume 27 (1) January/February/March 2004 p. 52-64.

[v] Siperstein et al., 2007

[vi] Siperstein et al., 2007

[vii] Mulvihill et al., 2004

[viii] Dunlap et al., 2004

[ix] The After-School Corproration, 2005

[x] Dunlap et al., 2004

[xi] Workshop notes from Erica Newman. Workshop “Respectful Accommodations” (Mary Shea) After the Bell Rings: Developing your Kit for Including All Children. 3rd Annual National Conference on Inclusion. Kids Included Together. 4/19/07.

[xii] The After-School Corporation, 2005

[xiii] Dunlap et al., 2004